With global bird populations decreasing at an alarming rate, more and more birds are becoming rare. In this article, I’m presenting a list of the 11 rarest birds in the world in 2022. These birds are not the only ones listed as critically endangered that have no recorded sightings on eBird.

The information for this article was sourced from both the IUCN Redlist and bird sighting data from eBird. None of these birds have any recorded sightings on eBird, meaning they may in fact be extinct already.

1. Sulu Bleeding Heart

The Sulu Bleeding Heart is a ground dove from the Sulu Islands in the Philippines. These birds are extremely rare and may possibly be extinct. They are known only from two specimens collected in 1891 and have not been sighted with any certainty since.

These birds are endemic to the island of Tawi-Tawi, the southernmost province of the Philippines.

They are described as having bright metallic green feathers stretching from their foreheads and crowns down to their upper backs and sides of their breasts. They have a bright orange breast patch; the feature which gives them their name and is blood red in other species. Read more about the other bleeding hearts in this Birdwatch World article.

Their wing feathers are brown and they have white on the underside of their necks, turning to ashy gray on their bellies and becoming chestnut towards their vents.

Not much is known about the Sulu bleeding heart’s behavior, other than they are ground-dwelling and feed from the forest floor.

2. Javan Lapwing

The Javan Lapwing is around 27-29 cm (10.6-11.4 in.) long. A dark-colored lapwing with a black head, bright yellow wattles, and brown to dark black feathers.

These birds have not been sighted since 1940 and are possibly extinct. If you were to find one, it would be in western or eastern Java. In the past, they may have also been found in Timor and Sumatra.

Javan lapwings live in open areas near freshwater ponds and overgrown swamps. They were also found in wet cattle pastures and abandoned paddy fields.

These birds would feed on water-living insect larvae, bugs, beetles, snails, the seeds of aquatic plants, and fish when held in captivity.

Discover the equipment needed to find any of these birds in this article on my blog.

3. Negros Fruit Dove

The Negros fruit dove is a small dark green bird known only from a single specimen collected in 1953 on Mt Kanlaon on the Island of Negros in the Philippines.

The specimen that was collected from a large fruiting tree at around 1907 m (3600 ft) on Mt Kanlaon was a female. It has been suggested that this bird was merely a runt or a hybrid rather than a valid species but it is widely accepted as being an individual species.

Local hunters have described birds that fit the description of Negros fruit doves being shot in 1985 and 2008. A targeted search in 2010 however, failed to find any trace of the bird. A great deal of their habitat has been cleared so any population that remains would be very small.

4. New Caledonian Rail

The New Caledonian Rail is another species with no reported sightings since 1984, indicating that they may be extinct. As their name suggests, these flightless birds are found in New Caledonia.

These birds are 45-48 cm (1.5-1.6 ft) in length. They occupy dense humid forests and formerly forested river valleys near the coast. They are now thought to exist in relatively inaccessible areas which is why they have not been sighted.

120 local people were interviewed between 2003 and 2006 but they did not provide any credible reports of the birds. Their populations may have been thinned out by introduced species such as dogs and cats. They reportedly have a tendency to crouch when chased which makes them vulnerable to dog attacks.

5. Tuamotu Kingfisher

The Tuamotu Kingfisher exists in very small numbers on a specific island in the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia. It is also called the Mangareva Kingfisher as a population originally existed on Mangareva Island but is now extinct.

These beautiful kingfishers are now restricted to a 26 km2 atoll called Niau. According to birdsoftheworld.org, the latest surveys completed between 2006 and 2008 suggest the population of these birds is around 125 individuals.

Tuamotu Kingfishers live in woodland, coconut plantations, and village gardens. Their diet consists of insects, larvae, and small lizards. They will also catch fish in reef ponds at low tide.

6. Makira Moorhen

It is estimated the population of Makira moorhens is around 50 individuals. There have been no confirmed sightings of this species on the island of Makira in the Solomon Islands since 1974 when locals claimed to have seen it.

The Makira moorhen is around 26.5 cm (10.4 in.) in length with a dark bluish slate head, neck, and breast. The feathers around its face and chin are almost black. Its wing feathers are brown to black in color. Their feet and bills are bright scarlet.

The only specimen of this bird was captured in December of 1929 in the central mountains of Makira at an elevation of 580 m (1902 ft). That area has primeval forests with dense undergrowth on steep slopes. The mountains of Makira reach 1200 m (3937 ft) and contain many streams and creeks but no standing water.

The exact reasons for this bird’s decline are not known though habitat destruction is likely a cause. Fire ants, introduced to the Solomon Islands in 1972 are known to attack the eyes of domestic animals and may have had some impact on Makira moorhen populations.

Discover how birds use ants in a positive way in this article here on the blog.

7. Buff-breasted Buttonquail

The buff-breasted buttonquail is a small bird known to exist on the Cape York Peninsula in northeastern Australia. They are around 18-22 cm (7.1-8.7 in.), mostly sandy brown, with yellow eyes and a gray crown, nape, and hindneck.

These birds can be found in wooded grasslands and the grassy fringes of forests and swamps. Also often found on stony hillsides with little to no grass cover or leaf litter.

Buff-breasted buttonquails are listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Redlist. Their population is estimated to be around 500 individuals.

As with all the other birds in this article, these birds have no recorded sightings on eBird.

8. New Caledonian Owlet-nightjar

The New Caledonian owlet-nightjar is a species that may be extinct as it has not been sighted since November 1998 in the Ni-Kouakou Reserve, south New Caledonia.

The entire plumage of this bird is brown with grayish-white barring. Only two specimens of this bird are known to exist; one was collected in 1880 and another dated 1913 or 1915. The specimen from 1880 flew in through an open window of a house in the village of Tongué in south New Caledonia.

Search efforts and local interviews conducted between 2002 and 2007 failed to find or provide any evidence of these birds. The lack of sightings at known sites suggests these birds may be extinct.

The most recent record of the New Caledonian owlet-nightjar was from a humid forest at an altitude of 1000 m (3280 ft). This bird was seen in the sub-canopy of the forest and was thought to be foraging as it appeared intermittently.

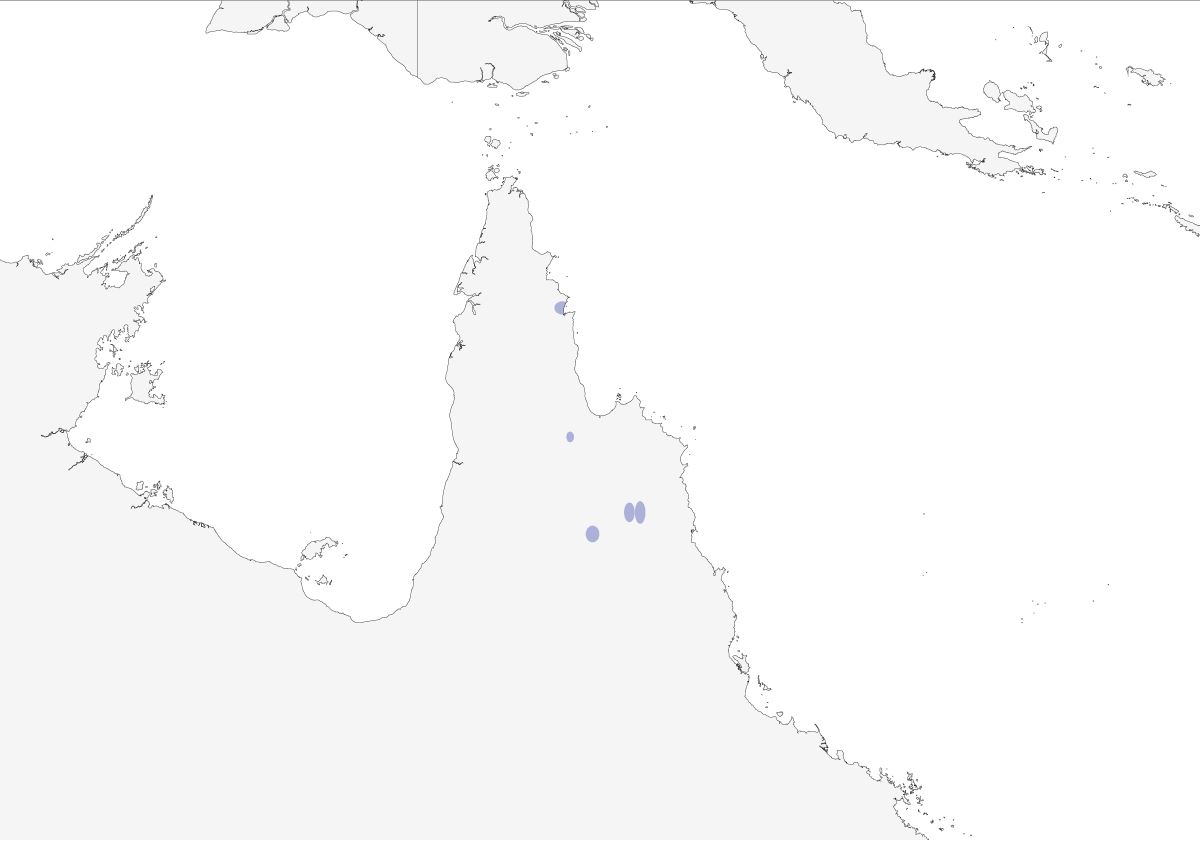

9. Turquoise-throated Puffleg

Only one unconfirmed sighting in more than 150 years confirms the existence of these tiny hummingbirds. Four specimens were collected in northwestern Ecuador and two skins also exist that were possibly acquired in southwestern Columbia.

Unfortunately, this species inhabits a very small range where the natural vegetation has almost entirely been destroyed. The only specimen that has data about where it was found is from Guayllabamaba, NW Ecuador where the terrain used to consist of dry ravines with montane dry forest and scrub, all but destroyed now.

Meet some other South American birds in this article here on the site.

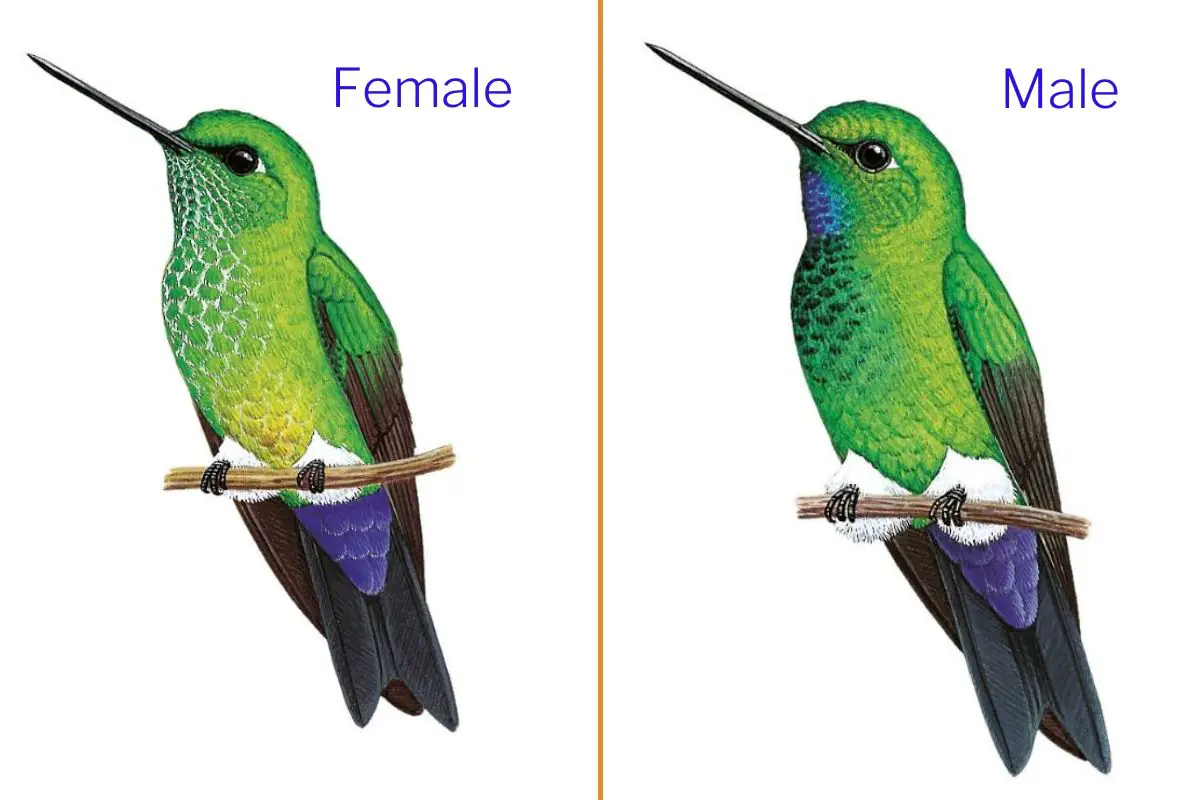

These birds look very similar to the Glowing Puffleg (pictured below) and would likely eat nectar from plants with short corolla tubes and insects.

10. Maui Nukupuu

As their name suggests, these tiny honeycreepers are endemic to the island of Maui in Hawaii. They were first observed between 1892 and 1896. There are no records of any sightings for 70 years after this. There have been unconfirmed sightings from 1967 to 1997.

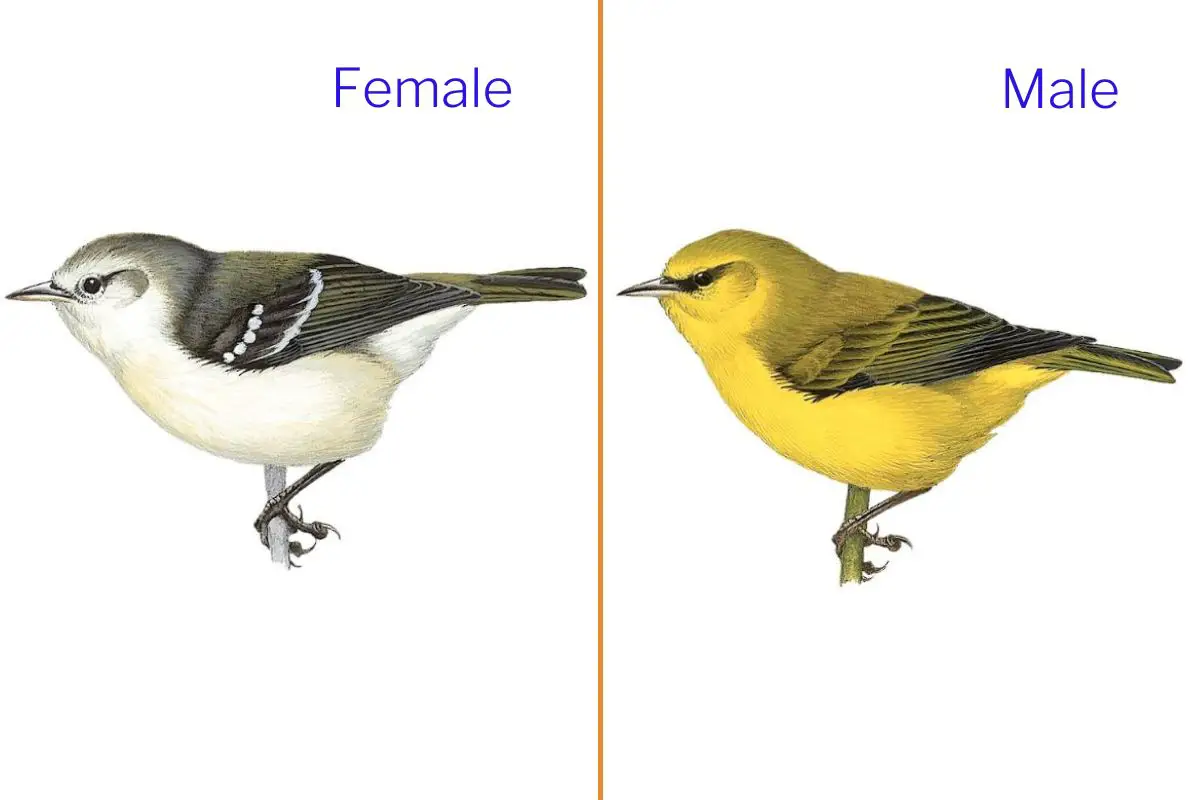

In 2001, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared the Maui Nukupuu most likely extinct but if their numbers are extremely low, it would be hard to find them in the dense montane mesic forests they inhabit. They are also very similar to Amakihi (pictured below):

If you were to find one of these birds, it would be in montane mesic forests with many Koa and ‘Öhi‘a-lehua trees. They would most likely eat insects and spiders, probing the bark of trees with their hooked beaks.

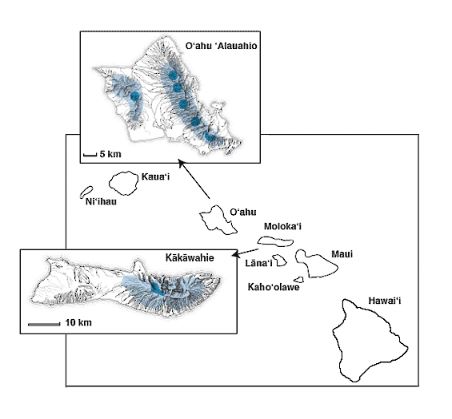

11. Oahu Alauahio

The final bird on our rarest birds in the world list is the Oahu alauahio (pronounced oh-AH-hu ah-lau-ah-HEE-oh). These are honeycreepers and are surprisingly similar to the Maui Nukupuu above.

These birds are found only on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. They were discovered in 1836-1837 and were common in the 1890s. By the late 1930s they had become rare and the last probably sighting was in 1990 in the north Hälawa Valley.

There are two other species of alauahio, found on the islands Maui and Läna’i, and Moloka’i. The Maui alauahio is common and has been sighted 1942 times so far this year according to eBird data.

The Oahu alauahios are 11.3-12.9 cm (4.4-5.1 in.) in length with bright olive plumage (males). They are known to eat invertebrates such as beetles but have never been observed feeding on nectar.

Conclusion

Though it is possible that all of the species listed in this article are extinct, I hold out hope that they are out there somewhere, waiting to show themselves to some unsuspecting birder. Most of them exist in dense or inaccessible forests which makes studying them very hard to do.

The decline of these and other bird species can be attributed to many things but habitat destruction and degradation are major factors. It saddens me to think how much of the world’s natural habitats we have destroyed. Even in 2022, it seems that we are not learning fast enough about the impact of such actions.

The work the IUCN does in data gathering, analysis, research, field projects, advocacy, and education is invaluable. Their efforts give us a measured, although decidedly grim view of the natural world.

We must continue to work towards a better world for all birds, plants, and animals. It is not only crucial to their survival but also our own.

To donate to the IUCN Redlist please visit this page.